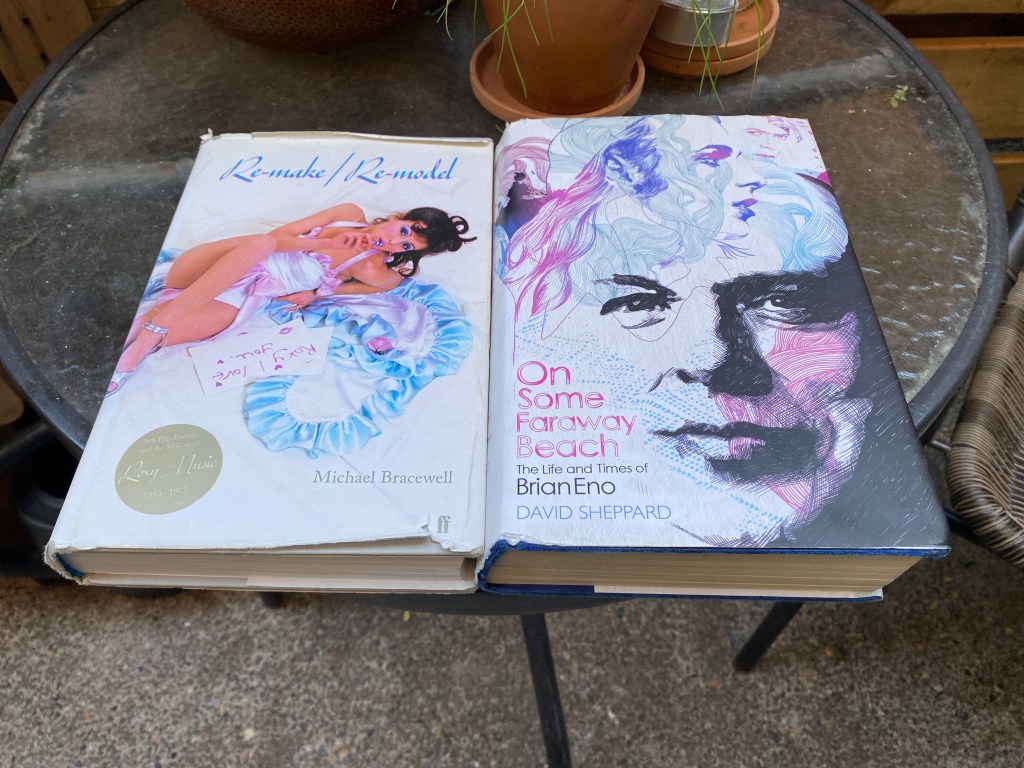

‘Taking the Sculpture off the Plinth’ is an inspiring statement relating to the changing dynamics of contemporary art, coming from the late 1960s[1], voiced by the artist Anne Bean, which I recently discovered in Michael Bracewell’s book, Re-Make/Re-Model: Art, Pop, Fashion and the Making of Roxy Music. Bean was a member of the art performance group, The Moodies. The group also included singer and performer Polly Eltes, who played a key role in the creative scene which produced the early makings of Roxy Music. Bean went on to be a pioneering performance artist in her own right, and as a member of the Bow Gamelan Ensemble with sculptor Richard Wilson and drummer Paul Burwell, during the mid-80s and 90s.

The Moodies didn’t last long as a performance group, but key enough to be mentioned in the story of Roxy Music. Their grounding through and connections to art schools for Brian Eno, Bryan Ferry, and the whole scene was an important component to what went on and into the future. Bracewell lays out the background and the various players with much conviction and confidence. He implies that it was the ‘sliding doors’ moment of Richard Hamilton, Bryan Ferry, Brian Eno, Anthony Price, Andy MacKay, Alan Lancaster and others, and their individual creativity, skills, visions and passions which would combine to create not just an art-rock band for a few years (before they became established pop musicians), but a new way for art, music and culture to be produced and experienced. It was a new way of doing things. Some core influences and ideas came from their particular art school experiences through radical teaching ideas and methods by particular tutors. Some tutors invariably got sacked or moved to other departments, when their ideas and influence were seen to challenge the traditional methods and presumed outcomes when making art (particularly painting and sculpture).

Brian Eno was introduced to the ‘Process not product’[2] mantra by tutor, Roy Ascott when he was at Ipswich College, which was a core idea and motivation as he pursued his own work in art and music. Eno’s insistence of being a non-musician, but systematically becoming a very successful music producer and generator of new music concepts and production, much to the chagrin of Bryan Ferry, shows how these early counter actions and concepts on a young mind can last a life time. Ferry made the decision to be a ‘proper’ musician, as opposed to being a painter early on, so chose to develop his art through a more traditional musical career.

Coincidently, in European art museums and galleries in the late 1960s, sculptures were literally coming off the plinths everywhere. A sculpture no longer needed to be elevated on a grand platform, like a precious gem. Pioneering independent curator Harald Szeemann’s seminal exhibition ‘Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Became Form” at Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland in 1969,[3] exhibited work by mainly male artists who had made their art directly in the museum spaces and outside of the building. Artists such as Richard Serra and Robert Morris, were using the floor and walls, to install and ‘display’ their sculptures. The actions of Lawrence Weiner and Barry Flannigan, were tearing up the building’s structure and depositing materials directly on to the galley floor.

Anne Bean was probably speaking metaphorically, with her statement. Art was still seen as a unique and precious commodity, rather than a concept to connect the artist and their artwork with the audience. It could have been, ‘taking the painting off the wall’ but how and where would you be able to experience this? In practical terms, paintings need some form of structure to hang on, to be a viewed as a painting. But what happens when it is not one thing or the other?

American artist Jessica Stockholder’s contemporary artworks are a combination of the 2 and 3 dimensional. They are installations and sculptures that are attached to the wall at some point of their form. Stockholder considers them paintings as much as sculptures. Made from vast amounts of various materials: wood, fabrics, carpets, fridges, discarded electrical equipment, oranges; the artwork is definitely off the plinth, only to be contained by the physical boundaries of the gallery.[4]

Pop artist Robert Rauschenberg also constructed his art or ‘combines’[5] with whatever form and materials that were available. His art was a healthy mix of printmaking, painting, sculpture, installations, which challenged the traditions of art production. He would willingly use the garbage that he systematically found when he walked around the block in New York near his studio. Picking up whatever he found to use in his art.

Richard Hamilton was the pioneering British artist and teacher who is credited with influencing the young Bryan Ferry with ideas, concepts and creativity from pop and ready-made art. Hamilton was unique in his acceptance to determine the art through its process, and the requirements of the concept, as opposed to just creating more of the same. His art was formed from an array of technical and creative methods and systems. He is contentiously labelled as the artist who termed ‘Pop’ in pop art,[6] even although his art was initially what could be termed, pop, as it featured images from advertising and popular culture, he produced work in relation to science, design, architecture and literature.

Hamilton was also a keen follower of Dada and conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp. Hamilton would remake the Duchamp work, ‘The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)’ 1915-1923, in a way which mirrored the copying or as Hamilton preferred ‘reconstruction’ of a great master’s painting. Hamilton would also call on the assistance of some Newcastle University art students to help him complete his version in 1965.[7] Ferry was also a Duchamp fan, taking the idea of the art ready-made into pop with his first solo album “The Foolish Things’ 1973 which included ‘ready-made’ personal pop standards by Bob Dylan, Rolling Stones, Lesley Gore, The Beach Boys and others.[8] He also titled his 1978 solo album, ‘The Bride Stripped Bare’, directly using part of the Duchamp work’s title.

Therefore, does it just take an opposite view, a counter movement or a different sequence of priority to create a new art. In pop music this was the case, countering what went before as a youthful no-taker of the existing tradition. By turning things on their heads, it makes new things happen. Taking that sculpture off of its plinth was a rallying cry, but it also needs a change of our own minds and acceptance of the unknown to make it work.

[1] Bracewell M. Re-Make/Re-Model: Art, Pop, Fashion and the Making of Roxy Music. London: Faber and Faber; 2007. p. 302.

[2] Bracewell M. p. 250.

[3] Müller H.J. Harald Szeemann: Exhibition Maker. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz; 2006.

[4] Schwabsky B. Jessica Stockholder. London: Phiadan Press; 1995.

[5] Rauschenberg Foundation. https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/art/galleries/series/combine-1954-64

[6] Bracewell M. p.76-77.

[7] Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/26/through-the-large-glass

[8] Ferry B. These Foolish Things LP. Island Records; 1973.